I'm the member of the Zolder Writers who moved from the Netherlands to Nashville. I left behind my fabulous critique group (along with wheels of cheese larger than my head and beautiful coffee shops where everyone can be a stoner with style) for the land of rhinestone cowboys and Ke$ha. A fair trade, but I still long for the old country... and for, in fact, anything old.

I'm the member of the Zolder Writers who moved from the Netherlands to Nashville. I left behind my fabulous critique group (along with wheels of cheese larger than my head and beautiful coffee shops where everyone can be a stoner with style) for the land of rhinestone cowboys and Ke$ha. A fair trade, but I still long for the old country... and for, in fact, anything old. While I write all forms of fantasy (magical realism, interplanetary, fairy tale, you name it, I've written it), my first love is history. History shows us where we as a collective species have been, and lets me judge better where we're going. But I'm not talking about historical fiction, which is fun but pain in the you-know-where to write (take it from me - I have a two-part historical fiction novel moldering on my hard drive), but the fiction of history.

Let me confess-- I'm the 20-something girl with huge-framed glasses and a quirky haircut who liked vintage books before they were cool. Well okay, that's a lie. They aren't cool. I don't think they ever will be cool - that's why you

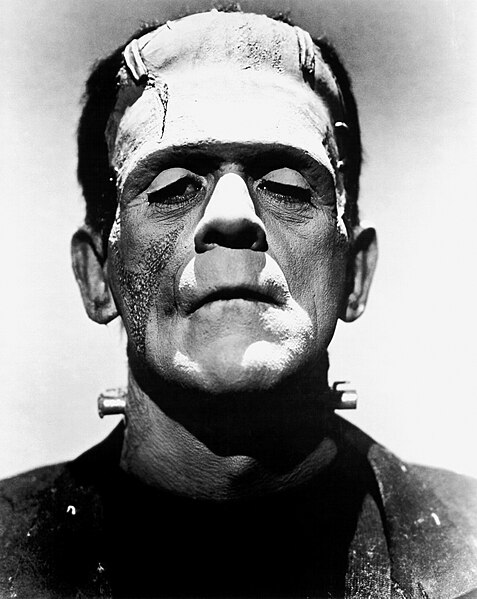

can buy 20 of them for a dollar at most used book stores, yard sales, and on Ebay. Which "them" am I talking about? The genre I would have never learned about in school: the vintage Gothic novel, which is really three genres in one, as each of these is a mystery/suspense with elements of old-school horror, and contains the obligatory romance. I don't mean books like Wuthering Heights (though I have no doubt it is the book that has inspired this genre) or Frankenstein (though that book is awesome. If you haven't read it, it's nothing like it is portrayed/parodied in Scooby Doo, it's a very complex and creepy book that questions the core of humanity. Get in there!). I mean the yellow-paged soft cover cheap pseudo-mysteries my grannies might have read.

can buy 20 of them for a dollar at most used book stores, yard sales, and on Ebay. Which "them" am I talking about? The genre I would have never learned about in school: the vintage Gothic novel, which is really three genres in one, as each of these is a mystery/suspense with elements of old-school horror, and contains the obligatory romance. I don't mean books like Wuthering Heights (though I have no doubt it is the book that has inspired this genre) or Frankenstein (though that book is awesome. If you haven't read it, it's nothing like it is portrayed/parodied in Scooby Doo, it's a very complex and creepy book that questions the core of humanity. Get in there!). I mean the yellow-paged soft cover cheap pseudo-mysteries my grannies might have read. You can immediately identify these books by the bad artwork on the cover. There is always a beautiful

These books were big sellers in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, though publishers continued to churn these out well into the 80s. They were written by women who grew up in the oppressive postwar 1940s and 50s, and then tried to reconcile the way they were raised with the wave of upcoming feminism in the 1960s. Their books are a fascinating insight into the mind of women struggling to find their place, and how to relate with men in light of how their own past meshes with women's lib.

Many of these vintage Gothic books are also historical novels, meaning that they were written about an earlier era than the publication date. Reading them now, 40-70 years later, is like reading double the history. There's nothing like seeing how a woman from the 60s with her mores envisioned gender relations in the past. In the case of men like Peter O'Donnell writing under a female pseudonym it becomes even more interesting - how would a man writing as a woman of the 50s and 60s perceive of gender in the past?

Beyond gender the themes of colonialism and empire are also strong. Many of these books, like Moonraker's Bride, by Madeline Brent (Peter O'Donnell) deal with Britain's colonial heritage and how it

influences gender. In this gripping tale, English narrator Lucy Waring grows up in a Chinese Orphanage on the eve of the Boxer Rebellion. At age 17 she is sent to England for safety, and is plunged into the familiar vintage Gothic romance/mystery setting of a creepy mansion filled with double-crossing distant relations with a sordid past and surprising ties to the events unfolding abroad, fighting over an uncertain fortune. While the young narrator must sort through all the lies to find the truth, she must figure out which of her relatives are the double crossers, and choose between potential suitors. But can she listen to her heart when one of these said suitors wants to plunge a dagger into it? Maybe the people she knew in the Chinese orphanage hold the key to the answers she seeks. (Not Maybe, definitely. They definitely hold the key to the answers - that's how these novels work.)

influences gender. In this gripping tale, English narrator Lucy Waring grows up in a Chinese Orphanage on the eve of the Boxer Rebellion. At age 17 she is sent to England for safety, and is plunged into the familiar vintage Gothic romance/mystery setting of a creepy mansion filled with double-crossing distant relations with a sordid past and surprising ties to the events unfolding abroad, fighting over an uncertain fortune. While the young narrator must sort through all the lies to find the truth, she must figure out which of her relatives are the double crossers, and choose between potential suitors. But can she listen to her heart when one of these said suitors wants to plunge a dagger into it? Maybe the people she knew in the Chinese orphanage hold the key to the answers she seeks. (Not Maybe, definitely. They definitely hold the key to the answers - that's how these novels work.)These books are like serious crack to my soul. I love them more than hipsters love PBR. Most of them stick closely to the formula, and even those written in the author's present-day time period often involve a foreign theme. What's most important, is that the narrator be plunged into an entirely new situation - new country, new relatives, and a new creepy formerly-bustling manor now desolate and in a state of decay and disrepair. And the details! The details are what make it. For example, in Moonraker's Bride, the mansion is named "Moonrakers" because it was once inhabited by some batshit-crazy relatives who would see the reflection of the full moon in the inky waters of the lake on the estate and one of them drowned using a rake trying to capture it. And this becomes the heritage of the people with whom our Lucy Waring deals. Every single person in that book spoons liberal portions of the insanity- flavored porridge for breakfast, and it's undeniably engrossing.

Most Gothic romance/mystery/suspense/horror stories written in the mid to late 20th century also feature an

And all of these clichés wrapped into one book are incredibly satisfying because the books are so cut and dried. The main character gets terrified, finds her courage, and figures it all out in time to have a satisfying relationship with a broody dark man (bonus points if this man is a sexy sailor like Captain Rex

This sort of neatly-wrapped ending is totally taboo in today's novels. Nothing is allowed to be neat. We aren't allowed proper happy endings anymore. All endings now have to be unsatisfactory or tinged with bittersweet. No antagonists are allowed to be unremorsefully evil - they always have to be complex. We always get to see what made them evil, and we sympathise because we know we ourselves might have been made evil under those circumstances. A compelling villain is one whose good motives led them down dark paths, and who therefore still have the potential to be redeemed right up to the very end of the book. In the vintage Gothic novels, however, evil is purely selfish evil, only masquerading as good. And evil gets what it deserves. It's simplistic and wholly satisfying on a whole other level. I could never write something like this, but don't judge me for devouring it until you've tried a few yourself.

So many interesting ideas here... I read every single dime store novel I could find when I lived in Iran. I was always struck by the way the writers constructed their world and how interesting it was to read novels that did not endure the test of time. Instead, they were what people read while traveling and left behind in hotel rooms. It was an eye opener.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely. By this point in time, they can be considered historical artifacts which signpost culture in the way only flimsy literature can. While hardly anyone would enjoy these books for their literary merit, the attitudes reflected in the characters is completely absorbing to me. It's mind-blowing to think that the way these characters think is the way my grandparents might have thought when my parents were children.

DeleteSo true! What surprised me was not the gender norm conformity (which I expected), but the ways in which it deviated from the norm and the ways in which the norm was policed. Does that make sense?

DeleteIt makes 100% sense. I think that we forget that women who live in oppressive regimes (not that I mean to imply American/British parity with Iran, though each country has a past which involves legislation that limited/s women) are more badass than we give them credit for. Strong, determined Women don't let laws and mores stop them, and authors acknowledge that in their books.

DeleteOr rather, I should say - strong women have never allowed laws and mores to stop them.

Delete